In his movie Psycho,, Hitchcock famously had Marion Crane, played by the movie’s biggest star Janet Leigh, murdered in the first third of the film. The audience was given a point of entry through a protagonist and then she was eliminated with two-thirds of the film left to go. Through careful manipulation, Hitchcock managed to attach the audience’s now untethered sympathy to the boy-like innocence of Norman Bates.

The first step was simply to give Norman screen time. Immediately after the murder, we watch Norman clean up the bathroom in what is almost real-time. In a basic and primitive way, screen time equals sympathy. It's not a perfect equation, but it is often the case that no matter what the character is doing if he or she has a lot of time on screen we begin to identify with them. In making The Godfather, Coppola and Brando convinced themselves that they were creating an anti-mafia film but you can’t allow the villain a lead role and expect us to despise him. There are exceptions like American Psycho or Maniac, but in general, you can count on the protagonist having considerably more screen time than the antagonist. The more we learn about Darth Vader the less we hate him.

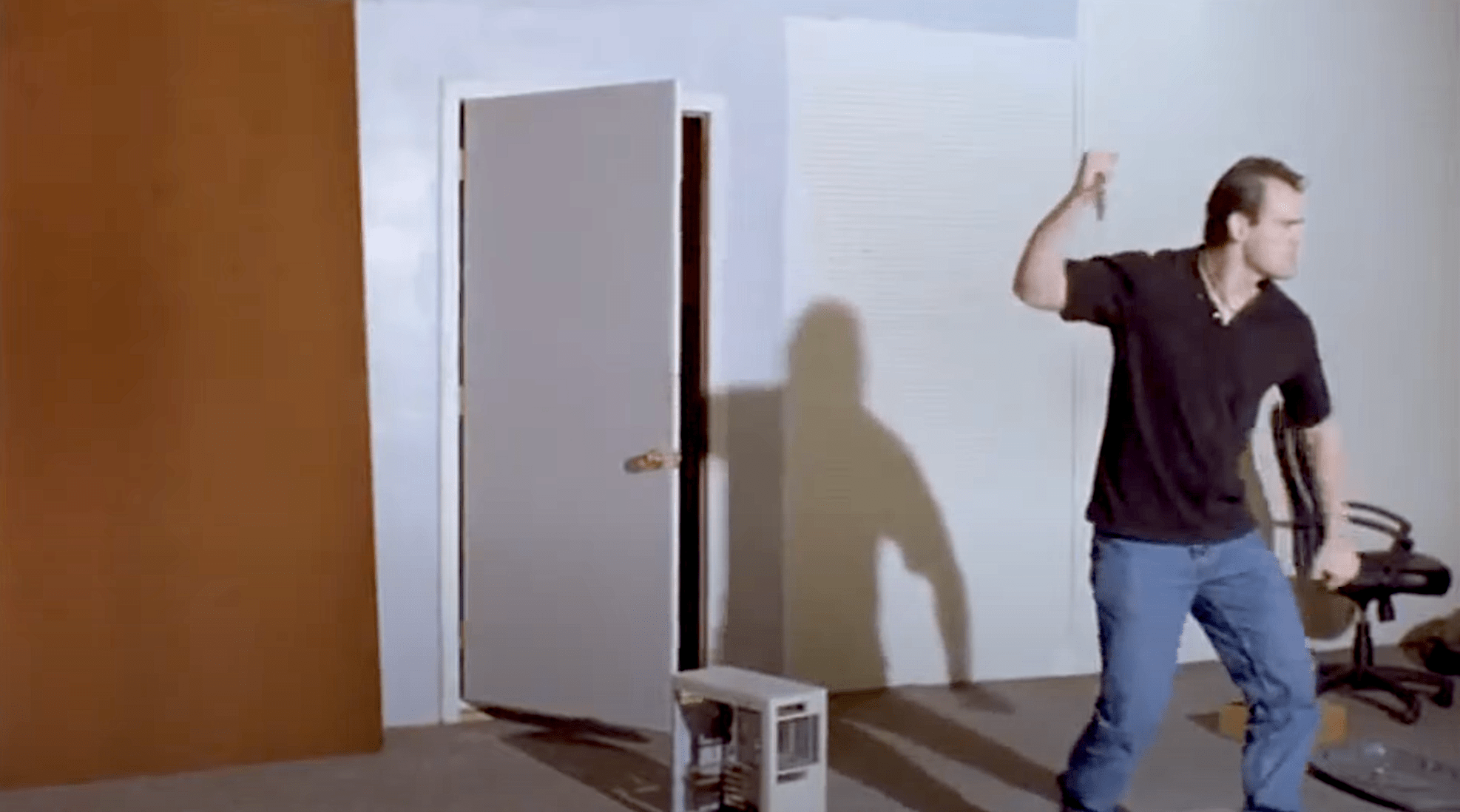

The other potent tool in Hitchcock’s toolbox was harassment. Have a character harassed by someone and it will quickly bond the audience to the victim. Marion Crane is harassed by several people before her demise, and once Norman is established as the new protagonist he is immediately harassed by a detective.

All these manipulative tricks and more are present in both Jordan Peele’s Us and Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite. Us begins with a straightforward set of protagonists that are easy to like and easy to identify with. Parasite sets itself a challenge by giving us a family of not-so-lovable con artists as our entry point, but by their appearing on screen first they have a leg up on our sympathies. It’s that simple. The word for protagonist comes from the words “first to act.” To solidify our sympathies Joon-ho has a stranger piss on the family’s house providing the needed harassment and then once we are invested in the family’s con we root for their success.

Hitchcock plays a shell game where different characters gain our sympathy. The game eventually reveals itself and is resolved, but for Peele and Joon-ho the shell game only gets more confusing as it progresses and by the end no resolution is possible. Resolution is one of the major markers that differentiate earlier American film from the modern era. No matter how dark noir films darkened, or how twisted Hitchcock films turned, or how bloody Christopher Lee’s fangs glistened the audience could count on resolution. In fact, there was a censorship board to police just this purpose.

In both Parasite and Us, we have “under people” and “over people.” This provides both a literal and figurative framework from which to begin. In Us, the “under people” or “tethered” are first introduced as terrifying antagonists without any hint of sympathy. They are meant to fulfill the role of the “other” that is crucial to any horror film. Jason, Michael Meyers, Freddy, Chucky, Dracula, Alien, and Pin Head all threaten us with destruction delivered not by a peer but by something foreign that does not belong in our world. As far back as Nosferatu this “other” has had racial undertones. I am not accusing these movies of being racist, but they appeal to a kind of fear that is similar to the fear racists have of the “other.” We are frightened of being overrun. We are frightened of our blood being contaminated. We are frightened because they don’t look or act like us, and so we come to the clever title of Peele’s film. In Us the frightening “other” is presented with a confounding twist, they look just like the protagonists, throwing a wrench in the formula.

Even as the tethered attack and harass their human counterparts we slowly come to understand their motivations and eventually begin to sympathize with them. Peele sets up a more polarized antagonism and spends much of the movie dragging either side closer together. In Parasite Joon-hoo sets up an antagonistic relationship but it is far less extreme. There are appealing aspects to characters on either side of the divide. In the Park family, who play the role of the “over people” or rich family, we have the innocent young son and the vulnerable young daughter. The mother is less sympathetic but she is a source of comedy. In the Kim family, it is the son who is most sympathetic. His intentions are clearly positive, whereas his sister’s are far more venal.

In Parasite, we have two families shot in contrast but then a third family appears. Hoon is even lower than the Kim family both literally and figuratively. In both Parasite and Us, halfway through the movie, we are introduced to a subterranean cement bunker. Both are deep, labyrinthine, and without any human softness. The descent into these long-hidden spaces is tense and we worry about what we will find in such inhospitable environs but that same fear turns to pity when we realize that people had to live under these conditions. The addition of Hoon draws some of our sympathy away from the Kim family, who by this time has already become less sympathetic due to the escalating nature of their deception. Still, all the director needs to do is shove the Kims under the coffee table to realign us with them. As Mr. and Misses Park get busy on the couch, no one in the audience is hoping that the Kim family gets caught. Even though the Kims have displayed despicable behavior, a little danger keeps us bonded to them.

Unlike Psycho Both Parasite and Us have children in them. Children are an easy way to manipulate sympathy. Da-song’s innocence helps humanize the arks and also becomes a dark foil in the black humor of his birthday. Watching Da-song faint as his father is stabbed is a complex climax of manipulation. Are we sympathetic to the father even though he was behaving horribly? If not are we at least sympathetic to Da-song for having to relive his trauma? Or is it funny? Schadenfreude doesn’t quite explain it but there is probably some other multisyllabic German word for the feeling we get when we laugh at a boy witnessing his father's death.

The youngest “under boy” in Us seems feral, barely human. He even wears a mask making it easier for us to fear and hate him. When he is destroyed we are relieved because we are in the middle of a frantic climax but Peele manages to humanize him and his plight just enough so that as we watch the flames engulf him our relief is tinged with sympathy.

The “other” as an archetype is a blank receptacle into which we can place any struggle. Struggles over class or struggles over race, conflicts between humanism and technology, or the individual against the group.

The “other” is a placeholder for what we do not want to accept. Psychologist Harry Stack Sullivan wrote about our need to create an alternate identity, the “bad me” or the “not me.” I remember my psychology professor in college asking us if we could spit in a cup and then drink it back down. When the class squirmed in disgust he asked how the saliva in our mouths suddenly became, not only separate from us but disgusting. The negotiation of what you accept and include as part of you, and what you reject as outside of you is difficult and complex. Characters in film can traverse this border and become one of us or one of them. If we identify with them they get our sympathy and our empathy. If we do not accept them they become a source of anger and/or fear. Sullivan would identify these emotions as the functional objects themselves. We wish to disown our anger and fear, these are the traits of the not me. However, when we cut ourselves off from these primal emotions we give away our power and place it under the bed, or in the dark, or in the closet, where it stalks us waiting to be reintegrated.

The youngest “under boy” in Us seems feral, barely human. He even wears a mask making it easier for us to fear and hate him. When he is destroyed we are relieved because we are in the middle of a frantic climax but Peele manages to humanize him and his plight just enough so that as we watch the flames engulf him our relief is tinged with sympathy.

The “other” as an archetype is a blank receptacle into which we can place any struggle. Struggles over class or race, struggles between humanism and technology, or the individual against the group.

The “other” is a place holder for what we do not want to accept. Psychologist Harry Stack Sullivan wrote about our need to create an alternate identity, the “bad me” or the “not me.” I remember my psychology professor in college asking us if we could spit in a cup and then drink it back down. When the class squirmed in disgust he asked how the saliva in our mouths suddenly became, not only separate from us, but disgusting. The negotiation of what you accept and include as part of you, and what you reject as outside of you is difficult and complex. Characters in film can traverse this border and become one of us or one of them. If we identify with them they get our sympathy and our empathy. If we do not accept them they become a source of anger and/or fear. Sullivan would identify these emotions as the functional objects themselves. We wish to disown our anger and fear, these are the traits of the not me. However when we cut ourselves off from these primal emotions we give away our power and place it under the bed, or in the dark, or in the closet, where it stalks us waiting to be reintegrated.

Us is a blend of both identity politics as well as class. Parasite hinges less on personal identity and more on class, as much as those two spheres can be separated. In considering class and economics it is important to note that Korean and American ideas of class differ significantly. America imagines itself as classless. We are meant to be the land of opportunity where anyone, no matter how humble their birth, can rise to the highest of statuses. True or not this is the socio-cultural belief. To bring up the issue of class, and the entrenchment of status is to defy this American belief system. Us is a transgressive film in that it makes its lynchpin the separation of class as well as race and unleashes a chaotic nightmare born of and fueled by the very denial that such divisions exist.

Parasite also explodes into chaos. This explosion however is not so much due to the denial of class segregation, but due instead to the resentment and frustration of the lower classes bubbling over. The Kim family lives in a basement apartment but like all the masses of lower-class people in Korea, they are not hidden.

Please forgive me for going full academic here but Jaques Derrida’s interpretation of the Pharmacon fits this analysis perfectly. The ancient Greek word pharmacon had three meanings, remedy, poison, and scapegoat. It came from an ancient rite where the citizenry of Athens would drive out the corrupt and deviant people of Athenian society and then sacrifice them to purify the city. Derrida points out the triple meaning of the word and suggests that the victims of this ritual had to embody all three definitions at once even though they were contradictory. They must be labeled the poison so that they become the locus of the problem, but they also must embody the ritual by becoming the remedy through their expulsion. Most importantly they must be a connected and integrated part of society in order for their being shunned as aliens to be a successful act of purification. People who are truly alien to society have no effect on it. You have to be one of us in order to be an “other.”

If you enjoyed this article click here for more

www.filmofileshideout.com/archives/bong-joon-ho-michael-gondry-and-leos-carax-in-tokyo